Many years ago, I took my first solo road trip. I was very proud of myself for mapping out a route that took me through the western part of Kentucky and Indiana. I ended my trip with two nights spent at one of Kentucky's many lovely state parks, Pennyrile, near Dawson Springs.

I tell you this because for some reason during my stay there I decided it would be a fun experience to hike one of the park's many trails. It was my first experience with solo hiking (or really any hiking for that matter) and one that I won't be doing again. I took off on a very, very gentle quarter-mile loop through the forest. Soon after entering the woods it occurred to me that I was so alone, that no one knew where I was or would miss me if I didn't return to my room (at least until checkout time) and that if there was an axe murderer in the vicinity, he was probably just behind that tree! I told myself not to be silly and continued on stumbling over tree roots, tripping on the smallest rocks, swatting insects, and listening intently for that axe murder. Or even a bear...

Let's just say I couldn't see the forest for the fears.

I survived, of course. But I kept thinking of that experience as I read Bill Bryson's A Walk in the Woods, an account of his attempt to hike the entire 2100-plus mile Appalachian Trail that stretches from Georgia to Maine.

What was he thinking?

Mr. Bryson is one of my favorite authors and I would follow him anywhere - even along the grueling AT, as it is called.

As is his way, Mr. Bryson not only informs but entertains and causes one to smile, chortle, and laugh out loud at his shenanigans. He had a much worse time of it than I did on my little 1320-foot trek.

He sets off one fine spring day in March with his childhood (and terribly out of shape) buddy, Steve Katz. Soon, spring has turned to winter and they find themselves slogging through knee-high snow. They meet other intrepid hikers along the way. They despair of aching muscles, noodle dinners, soaking wet clothes, struggles with expensive and unwieldy equipment, a million irritating insects, rushing streams, a possible nighttime visit by a bear (never actually confirmed), and a multitude of other horrors that are to be experienced in the deep, dark woods.

And this was just the first day.

To be fair, every now and then along the way they were rewarded for their efforts with a fine view or a shower and a good meal when the trail happened to cross near a town. But most of the trip sounded totally exhausting. And, really, not all that much fun although Bryson makes it sound enticing in a masochistic sort of way.

I read A Walk in the Woods to further prepare me for reading Walden. I was amused to read Bryson's jab at Thoreau:

The American woods have been unnerving people for 300 years. The inestimably priggish and tiresome Henry David Thoreau thought nature was splendid, splendid indeed, so long as he could stroll to town for cakes and barley wine, but when he experienced real wilderness, on a visit to (Mount) Katahdin in 1846, he was unnerved to the core. This wasn't the tame world of overgrown orchards and sun-dappled paths that passed for wilderness in suburban Concord, Massachusetts, but a forbidding, oppressive, primeval country that was "grim and wild...savage and dreary," fit only for "men nearer of kin to the rocks and wild animals than we." The experience left him, in the words of one biographer, "near hysterical."

I feel your pain, Henry.

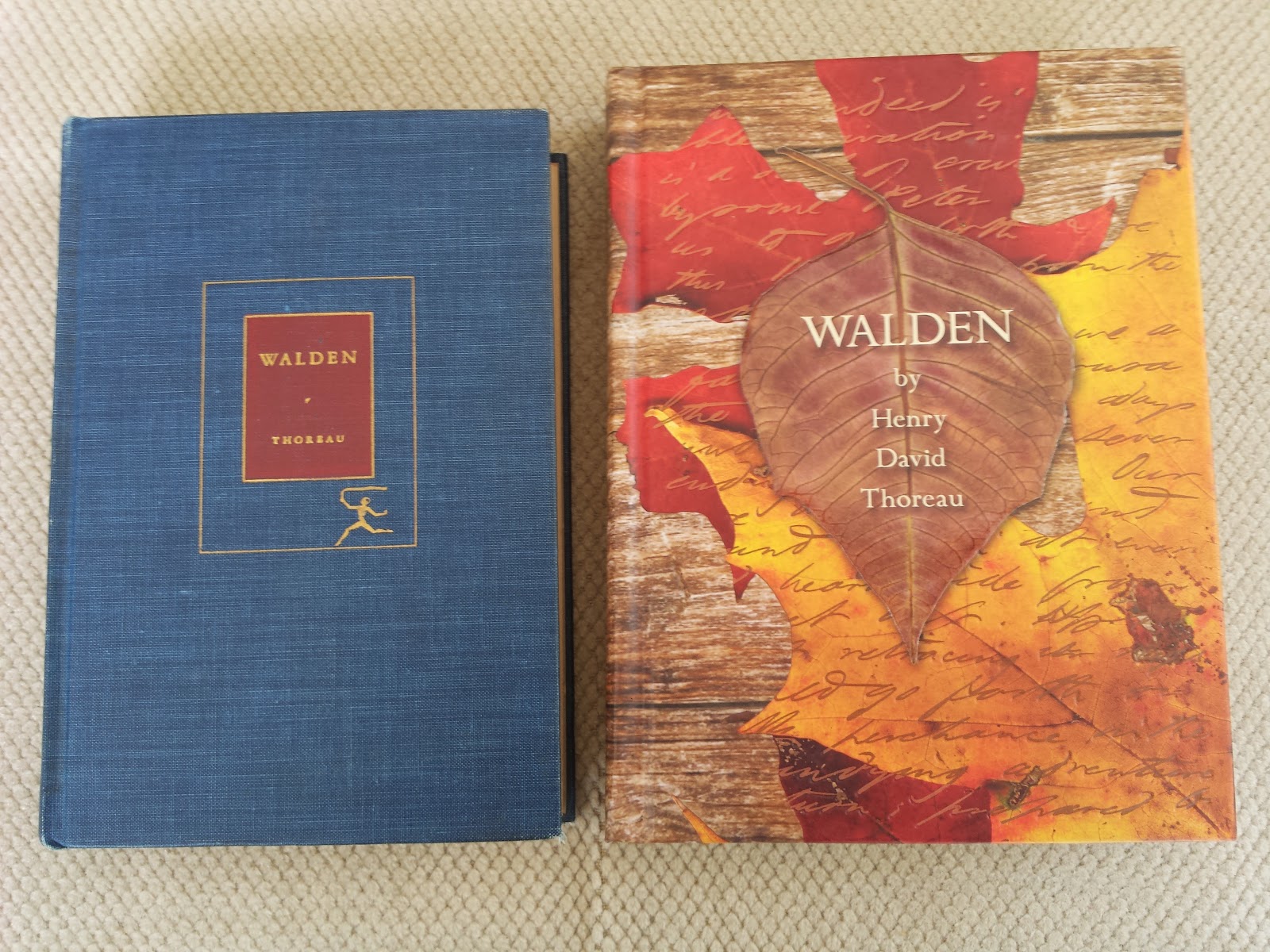

We bookish sorts can't always stop at having one edition of a certain book, so it might not surprise you to know that I have two copies of Henry David Thoreau's Walden.

One copy is a Modern Library edition (1937) that contains not only Walden, but Thoreau's Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, Walking, and Civil Disobedience.

The other volume contains only Walden and I bought it simply because I liked the cover with its autumn leaves and examples of early penmanship:

Even though these two editions sit on my shelves, I have yet to read Thoreau's account of his two years, two months, and two days spent in a tiny cabin on the banks of Walden Pond.

But, as August 9th of this year will mark the 160th anniversary of the publication of this classic, it seems a fitting time to finally hunker down and find out just what went on during those years in the woods.

In preparation for this occasion, I just finished reading Michael Sims's biography of this strange and brilliant fellow in The Adventures of Henry Thoreau (2014). The book looks at Thoreau's life growing up in Concord, Massachusetts, his wanderings in the forests and fields and his excursions on the waterways in the area, and his fascination with the tales of the native Americans who once hunted and lived on the very land that he now walked. I learned about his friendships with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other literary movers and shakers of the time. And, I found out that the first word in his first journal was Solitude.

Although Thoreau graduated from Harvard and taught school for a while he never really could settle down to a steady profession. He helped his father in the family pencil manufacturing business, did some tutoring, and took on a few odd jobs. Over the years, he became an abolitionist, spent a night in jail for refusing, on principle, to pay a state tax, wrote bad poetry, and kept on writing in his journals.

By the time Thoreau died of tuberculosis at the age of forty-four, Mr. Sims writes, "he had written two million words in this private storehouse, filling seven thousand pages in forty-seven volumes between October 1837 and November 1861."

The tale presented here is based on information gathered from letters and diaries of Thoreau's family and friends and the author has put together an informed look at the young man's searching for self and solitude. Mr. Sims has an intriguing way of bringing the reader into the time and place of Thoreau's world with historical details, sights, and sounds of that era. Reading this biography has certainly introduced me to this quirky fellow journal keeper.

And although I am certainly not off to build a cabin in the woods, I will open to the first pages of Walden and pretend. Care to join me?

Penelope Lively is a British author of award-winning adult novels and books for children. I had not read any of her works until I stumbled across her recently published memoir Dancing Fish and Ammonites.

Ms. Lively is 81. This memoir is not quite a memoir. She calls it "a view from old age." It contains her reflections on age (she speaks from experience) and memory, books and history, and the six possessions that she holds near to her heart and that "articulate something of who I am."

Although her look at her childhood growing up in Cairo and her take on the social changes that have taken place in England (and the world for that matter) in her lifetime were splendid to read about, it was of course her look at her books and her reading that especially intrigued me.

"I can measure out my life in books," she writes and begins with the enthralling tales of Beatrix Potter, the King James Version of The Bible, and Andrew Lang's Tales of Troy and Greece of her childhood, on through the romantic historical novels of her teen years, and the serendipitous reading of fiction in her adult years.

But in old age, she decides, the three titles she would pick for her desert island stash are Henry James's What Maisie Knew, William Golding's The Inheritors, and Ford Madox Ford's The Good Soldier.

Perhaps not my choices, I haven't read them, but like her spotlight on the six possessions that she cherishes, it prompted my own thoughts as to my favorites and keepsakes. I am still pondering these.

In addition to being a thoughtful read, I love the cover of this book. Every time I glance at the dancing fish - which are a representation of the leaping fish sherd she once found on the beach and one of her six things - I have to smile. They look so joyful.

It was fun reading The Hidden Staircase, starring intrepid detective Nancy Drew, from an adult perspective. I suspect that when I read the books chronicling Nancy and her adventures as a younger me, I glossed over many of the subtleties in my race to gather clues and reach the dénouement!

Oh, what I missed.

There are the domestic details: dinner beginning with sherbet glasses filled with orange and grapefruit slices followed by spring lamb, rice and mushrooms and fresh peas with the added delight of chocolate angel cake and vanilla ice cream. Or how about "steak and French fried potatoes, fresh peas, and yummy floating island for dessert."

Visitors are known as callers and are offered tea and sandwiches.

There is no calorie counting for our Nancy.

I enjoyed the scenes where Nancy and her friend Helen dress in Colonial costumes and wigs found in trunks in the attic of the "haunted" Twin Elms. This is the manor house where the girls are staying while trying to solve the mystery of the "ghost" that has suddenly begun plaguing Helen's great-aunt Miss Flora and great-grandmother, Rosemary. The two girls dance the minuet to the accompaniment on the spinet by Rosemary. There is a bit of early American history thrown in as well. For instance, I didn't know that during the Revolutionary War spies would take jobs as servants in a well-to-do home in the hopes of gathering information for the enemy.

In this well-told tale, Nancy and her father are almost run over, ceilings crash in, trap doors are discovered, there is a kidnapping and a car chase, the police always show up within five minutes when called by Nancy, and even misguided criminals come to see their wrong-doings thanks to the young sleuth's questioning.

The Hidden Staircase, number two in the series, was quite a romp. I will surely be reading more of these iconic stories, searching out details that I would have skimmed over in my youth. I will go back and begin with number one, The Secret of the Old Clock.